He returned to Anglicanism (“my tribal religion – the religion of the English who don’t believe a word of it”), but it is a moot point whether or not he was an atheist (as most of his secular friends insisted) or whether, for him, God was part of what he called “the web of seeming”, the “life-world” (Husserl’s Lebenswelt). He declared Thatcherism, with its free-market libertarianism, philistinism and contempt for education, “a betrayal” of cultivated Burkean conservatism, yet went on to support it. Indeed, lucid and clear-thinking though he was, it was difficult to know what he really did believe, and what trumped what in his multilayered thinking. What he said in his younger days opposing feminism, liberalism, egalitarianism, homosexuality and anti-racism could be seen, at the very least, as worrying, and was constantly invoked against him long after his stance had mellowed with age and his happy second marriage, or else it was denounced as self-publicising hyperbole. Scruton was the exact opposite of a champagne socialist: he took terrible risks for his political beliefs, not just literally, in eastern Europe, but in continually expressing outrageously reactionary views, which led him to be ostracised by the “leftwing establishment”.

all my hesitations about progress”, and defended authority and obedience.

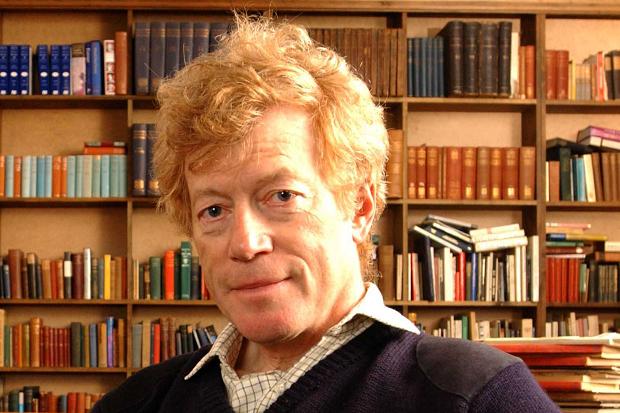

“I suddenly realised I was on the other side … wanted to conserve things, rather than pull them down.” He began to read Edmund Burke, who “summarised. His thesis formed the basis of his book Art and Imagination (1974).Īt the age of 24, he witnessed the événements of 1968 from a first-floor window in Paris, but, unlike his friends, was disgusted by the protesting students’ self-indulgent iconoclasm. Having changed from science to philosophy, he gained a double first in 1965, and, in 1973, a PhD in aesthetics. After the family moved to Buckinghamshire, he discovered the delights of high culture in Marlow library and from the Royal grammar school, High Wycombe, he won an open scholarship to Jesus College, Cambridge (for which, apparently, his father never forgave him). His was spun out of his life – often agonisingly.īorn in Buslingthorpe, north-east of Lincoln, Roger was the son of Jack Scruton, a teacher, and his wife Beryl (nee Haynes), and was brought up in a somewhat uncultured home. He exemplified Nietzsche’s aphorism that “every philosophy is a sort of memoir”. Scruton was made a fellow of the British Academy in 2008 and knighted in 2016. In 1995, he and the campaigner for constitutional reform Anthony Barnett, who described the two of them as “at opposite ends of the political spectrum”, set up the Town and Country Forum, to tackle rural issues. He was an ardent Green and countryside supporter – as well as a keen huntsman – declaring that, while environmentalism has all the hallmarks of a leftwing cause, it is in fact about conservation, equilibrium and “oikophilia” (love of home), therefore “quintessentially conservative”. He and his second wife, Sophie Jeffreys, and their children, Sam and Lucy, eventually settled down in what he sometimes dubbed Scrutopia, near Malmesbury, in Wiltshire. Scruton held academic posts at Boston University (1992-95) and the Institute of Psychological Sciences, Arlington, Virginia (2007-09) and he was visiting professor at Oxford University from 2010, and a professorial fellow in moral philosophy at St Andrews University (2011-14). As a result, he was arrested and thrown out of Czechoslovakia several times in the 1980s – and, after the collapse of communism, was awarded medals by the Czech Republic, Poland and Hungary. Under the codename Wiewórka, Polish for squirrel (“a tribute to my red hair”), he gave clandestine lectures, assisted dissident activism, and smuggled banned works (disguised as unused computer discs) into the Soviet bloc. In 1978, Scruton co-founded the Jan Hus Educational Foundation in Prague.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)